🧠 Einstein's Unconventional Selection of Disciples

In 1935, Albert Einstein, then at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study, was tasked with identifying young physicists who could help advance the frontiers of science. Officially, Einstein is famously—or infamously—credited with having no doctoral students under his guidance, leaving his mathematical and intellectual genealogy a curious anomaly. However, a closer look at his time at Princeton reveals that he did, in a sense, cultivate a cohort of intellectual disciples, using an unconventional method to identify collaborators.

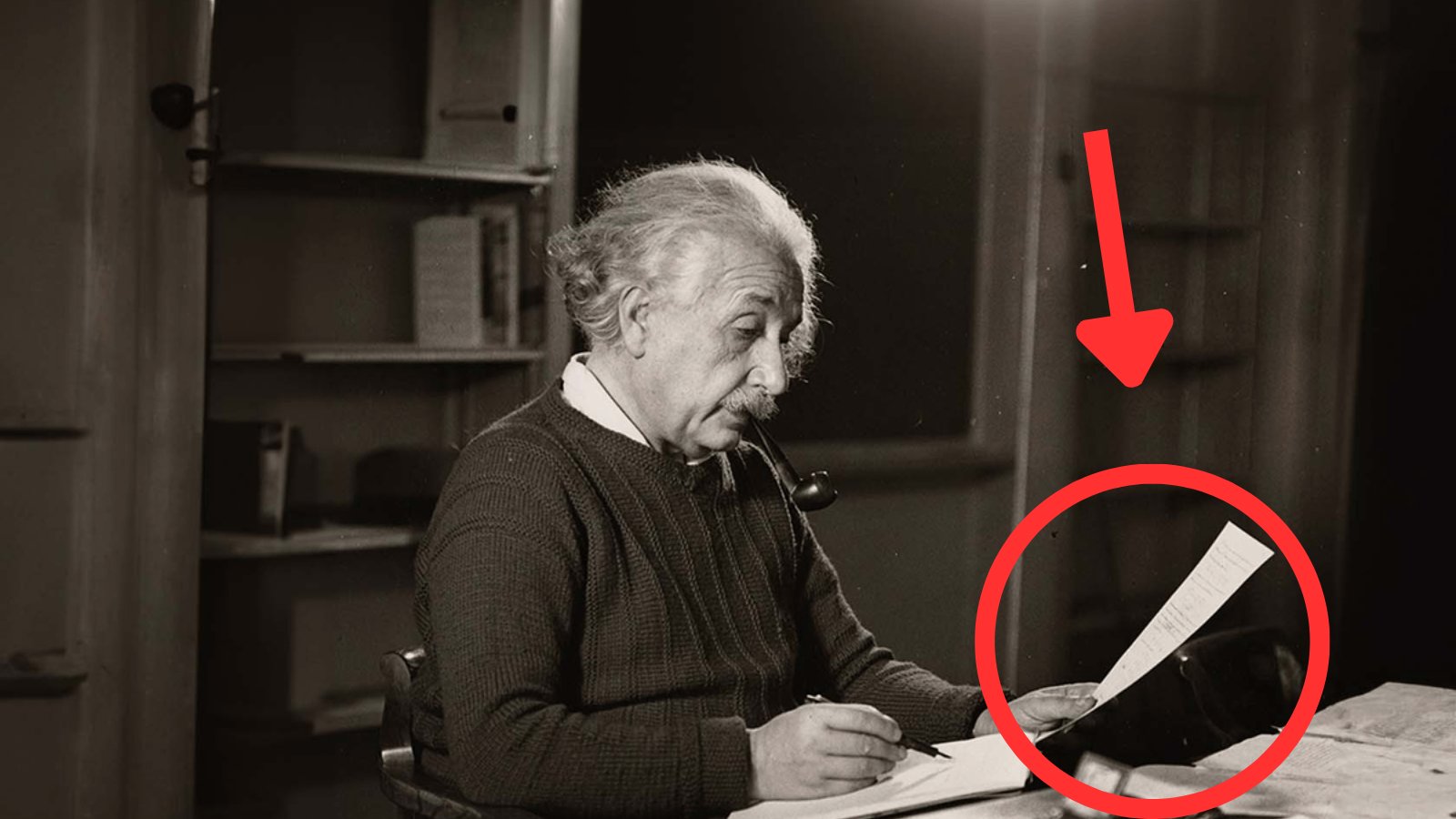

Einstein’s office was modest—a desk, a chalkboard, and an unusual collection of deliberately “wrong” physics papers. These flawed solutions to famous problems were the centerpiece of Einstein’s remarkable process for selecting collaborators. Candidates were asked to solve a well-known physics problem, after which Einstein presented them with one of his “wrong” papers. Their task wasn’t to correct the errors, but to react in a way that revealed their intellectual character.

Many candidates, though brilliant, took a conventional approach: they identified the flaws, cited the violated principles, and confidently dismissed the incorrect solutions. Einstein thanked them politely but never invited them back. For him, the ability to spot errors wasn’t the mark of a great thinker.

A select few, however, responded with fascination rather than dismissal. They would immerse themselves in the flawed solutions, asking, “What if this were true?” These candidates exhibited the ability to explore the implications of seemingly impossible ideas. Einstein called this mindset “productive confusion”—the willingness to embrace unconventional thinking and entertain the absurd. For Einstein, this was the hallmark of true genius.

Through this process, Einstein indirectly mentored a group of extraordinary individuals who became de facto extensions of his intellectual legacy. John Wheeler, one of his early selections, spent hours grappling with an incorrect quantum mechanics solution. Later, he went on to pioneer black hole physics and quantum information theory. Robert Oppenheimer, similarly inspired by Einstein’s “wrong” papers, went on to lead the Manhattan Project and revolutionize quantum field theory. These disciples, though not formally his students, carried forward his philosophical and scientific ideals, creating a unique intellectual lineage.

And here’s where the story gets personal. Through Wheeler, Einstein’s intellectual lineage is far from lost. Wheeler mentored Charles Misner (Princeton PhD 1957), who in turn mentored Vincent Moncrief (Maryland PhD 1972). Moncrief, as fate would have it, was my doctoral adviser at Yale (Yale PhD 2015). By this quirky intellectual genealogy, I too can trace my lineage back to Einstein, which is an amazing privilege. All glory to God!

**